My review of the luscious exhibition Heart On: Joyce Wieland was published over the holidays in PUBLIC Journal online here. Below is a version of the review that includes my documentation of the exhibition.

Ohhh, Canada… Joyce Wieland’s Erotic Citizenship

Joyce Wieland (1930–1998) made her first income as an artist at the age of eight. Noting her peers’ enthusiasm for comic books, an entrepreneurial Wieland drew and sold pinups of movie stars and naked ladies. Girls gravitated to glamour celebrity portraits, priced at five cents, while boys snapped up the naughty ones for ten. This early experience anticipated the most enduring features of Wieland’s expansive artistic career: Her responsiveness to vernacular visual culture; her attunement to women’s complicated positions as makers, consumers, and objects of desire; and her appreciation for the power of the erotic. Critical writing on Wieland’s work tends to emphasize the first two, but it is the third that pulsates to the fore in Joyce Wieland: Heart On, a joint exhibition between the Montréal Museum of Fine Arts and the Art Gallery of Ontario.

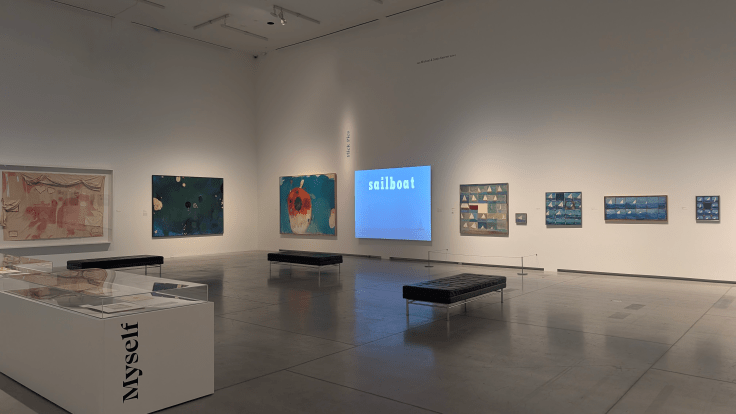

This long-overdue posthumous retrospective spans fifty years of Wieland’s prolific practice, gathering more than a hundred works across nearly every medium she employed: Film, painting, textiles, drawing, sculpture, and even an outdoor reconstruction of her 1982 public earthwork, Venus of Scarborough. The exhibition balances a chronological approach with thematic emphases, tracing Wieland’s lifelong commitments to cinema, domestic and feminine modes of expression, the iconography of Canadian nationalism, and environmentalism. The installation brings together Wieland’s dual legacies as a visual artist and experimental filmmaker, drawing attention to the layered connections between her works across various media. A looping projection of Wieland’s film Sailboat (1967) is paired with a series of sailboat paintings that experiment with the pictorial frame as a cinematic device. Nearby, found-object assemblage Cooling Room No. 1 (1964) uses plastic toy sailboats to stage a sculptural animated sequence; a turn of the head reveals a nude Wieland handling another toy sailboat in her sensual film Water Sark (1965).

What strikes me most in encountering Wieland’s assembled body of work is its emanating lustiness—sometimes in content but almost invariably in form. Parting lips, pendulous breasts, floppy cocks and their symbolic surrogates are scattered across Wieland’s oeuvre like naughty messages. Lipstick prints appear in various guises, almost a signature of the artist, coquettish and unapologetically messy. The Kiss (1960) draws the viewer’s attention to a thick smear of oil paint in the shape of a mouth positioned at face-height. A scratched arrow instructs the audience to interpret the smear as evidence of an amorous exchange, or perhaps it invites them to brazenly lock lips with the canvas. To make her iconic lithograph O Canada (1970), Wieland kissed each syllable of the anthem into a lithograph stone like a devotee, the greasy oil of her lipstick creating the foundation for the print matrix. The resulting print suggestively invites its audience to moan the anthem. Heart-on (1962), from which the exhibition gets its innuendo title, transforms unstretched canvas into a visceral burlesque of parted drapes, lifted bloomers, and secretive flaps. Heart symbols cluster like vulvas on smeared and torn fabric. The canvas is soaked and stained with crimson reds suggestive of menstrual or penetrative bleeding. The composition is achingly confessional, like an airing of dirty laundry, and yet private in equal measure.

The most seductive features of Wieland’s work, however, lie in moments of formal subtlety. In Arctic Day (1970–1971), she applies coloured pencil to stuffed cotton cushions with the softness of cosmetic blush, so that the precision of her wildlife illustrations is only apparent at a breath’s distance. The sculptural quilt, Canada (1972), seems at first to be a sanitary white, and yet each letter vibrates with a soft, saturated glow. Sneaking a furtive peek at a tight angle reveals the bright fabric sewn on the underskirt of each letter to create the sensitive chromatic effect. Even the artist’s more conventional paintings and drawings are not worked-upon; they are caressed and massaged, cinched and pierced, smeared and powdered—like skin. Surfaces are layered with pastel hues and adorned with small embellishments, rewarding intimate encounters. The exhibition design occasionally extends the artist’s penchant for the suggestive peek-a-boo. Her coloured pencil drawings of frolicking nudes, collectively grouped as the Bloom of Matter series (1979–1981), are enclosed in labial accordion walls and lit with a boudoir pink.

Wieland brought a playful, feminine eroticism to her many responses to Canadian nationalism. Her landmark 1971 show,True Patriot Love, at the National Gallery of Canada—the gallery’s first solo exhibition by a living female artist—opened during a time of renewed patriotic sentiment and political mythmaking. This period solidified contemporary Canadian symbolism, including the 1965 parliamentary confirmation of the maple leaf flag. Returning to Canada after years of living in New York, Wieland stuffed her exhibition with quilted, knitted, batted, and sewn maple leaves and other national emblems, using the iconography to both celebrate and satirize the fervour of centennial-era patriotism. Cheekily adopting an atmosphere of royal pageantry, the artist commissioned Arctic Passion Cake (1971) of sugar-coated Styrofoam (adorned with confectionary provincial coats of arms) for the opening and designed a musky perfume, Sweet Beaver: The Perfume of Canadian Liberation (1971), as a proposed national scent. The exhibition evoked the spectacle of a national pavilion, inviting visitors to experience Canada as a lady: A body of youthful, abundant fertility trapped between the tiresome paternalism of John Bull and the predatory overtures of Uncle Sam.

Wieland was not pacified by political assurances of Canada as a welcoming civil society. Instead, True Patriot Love drew attention to the exhibition’s political backdrop of Québécois separatism, state militarization of the Circumpolar North, Indigenous sovereignty declarations, women’s rights activism, and environmental warnings. Embracing textile materials and collaboratively made works, Wieland crafted a multifold national body politic threatened by the corporate-sponsored, government-sanctioned trafficking of natural resources.

True Patriot Love established Wieland’s reputation as a feminist commentator on Canadian nationalism—a reputation that Joyce Wieland: Heart On does not complicate despite similarities between her tongue-in-cheek approach and the self-deprecating character of mainstream Canadian pride. Nor does the exhibition and its accompanying publication wrestle with the settler romanticism permeating her enamoured vision of an unspoiled North. It does, however, demonstrate that the artist’s stylistic range across decades—a career that one critic of her 1987 AGO retrospective described as “unresolved” and lacking “subtlety of thought”1—amounts to a cohesive and generative trajectory. Heart On revitalizes and reasserts Joyce Wieland’s place in art history, expanding on smaller recent exhibitions that affirm her as a great Canadian painter, inventive East Coast Pop artist, and transatlantic feminist icon.

Following its predecessors, Heart On frames the significance of Wieland’s oeuvre by relating it to her artistic influences, peers, and collaborators—defining her as a key voice of her generation. Yet, as an accomplished artist included in landmark exhibitions since the 1960s, Wieland has also influenced Canadian art and experimental cinema for over a quarter-century, eliciting dozens of creative responses. For example, Brian Jungen’s Wieland (2006)honours the artist’s use of textiles to expose patriotic fetishism, while also deflating the settler feminism plumping up her work. Hazel Meyer playfully reinvents Wieland into a queer icon in her solo exhibitions The Weight of Inheritance (2020) and The Marble in the Basement (2024). These artists among others have tenderly embraced Wieland as an art matriarch while probing and diverging from facets of her work. Following the comprehensive foundation established by Heart On, I am eager to see future exhibitions address Wieland’s impact on subsequent generations of artists.

Wieland’s ability to expose the crafted metaphors and seams of Canadian identity through a plurality of media is particularly resonant at a time of heightened dissonance in national discourse, as institutional commitments to Indigenous Reconciliation are uttered in the same breath as a renewed patriotic zeal against the threat of American influence. Once again, politicians assert that Canada’s body is not for sale while extolling her bountiful territories and resources to an eager international clientele. Critic Susan Crean described Wieland’s erotic take on nationhood as “unashamed love without sentimentality.”2 Considered broadly across her oeuvre, it is also a search for national belonging without patriotism. Territorial sovereignty without possession. Devotion without submission.

- John Bendey Mays, “AGO Retrospective Enshrines the Myths Surrounding Joyce Wieland,” The Globe and Mail, 18 April 1987, C15. ↩︎

- Susan Crean, “Forbidden Fruit: The Erotic Nationalism of Joyce Wieland,” This Magazine 21, no. 4 (August/September 1987): p.17. ↩︎